Steve Jobs American businessman

Jobs was raised by adoptive parents in Cupertino, California, located in what is now known as Silicon Valley. Though he was interested in engineering, his passions of youth varied. He dropped out of Reed College, in Portland, Oregon, took a job at Atari Corporation as a video game designer in early 1974, and saved enough money for a pilgrimage to India to experience Buddhism.

Back in Silicon Valley in the autumn of 1974, Jobs reconnected with Stephen Wozniak, a former high school friend who was working for the Hewlett-Packard Company. When Wozniak told Jobs of his progress in designing his own computer logic board, Jobs suggested that they go into business together, which they did after Hewlett-Packard formally turned down Wozniak’s design in 1976. The Apple I, as they called the logic board, was built in the Jobses’ family garage with money they obtained by selling Jobs’s Volkswagen minibus and Wozniak’s programmable calculator.

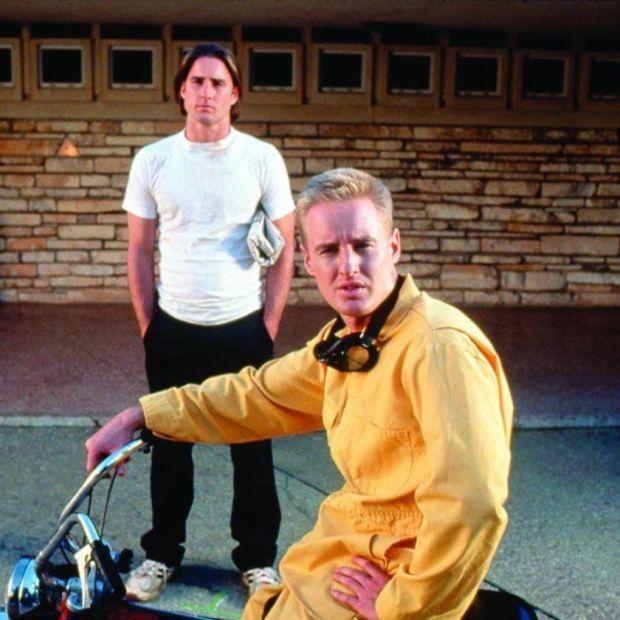

Steven Jobs (right) and Stephen Wozniak holding an Apple I circuit board, c. 1976.

Courtesy of Apple Computer, Inc.

Jobs was one of the first entrepreneurs to understand that the personal computer would appeal to a broad audience, at least if it did not appear to belong in a junior high school science fair. With Jobs’s encouragement, Wozniak designed an improved model, the Apple II, complete with a keyboard, and they arranged to have a sleek, molded plastic case manufactured to enclose the unit.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.Subscribe Now

Though Jobs had long, unkempt hair and eschewed business garb, he managed to obtain financing, distribution, and publicity for the company, Apple Computer, incorporated in 1977—the same year that the Apple II was completed. The machine was an immediate success, becoming synonymous with the boom in personal computers. In 1981 the company had a record-setting public stock offering, and in 1983 it made the quickest entrance (to that time) into the Fortune 500 list of America’s top companies. In 1983 the company recruited PepsiCo, Inc., president John Sculley to be its chief executive officer (CEO) and, implicitly, Jobs’s mentor in the fine points of running a large corporation. Jobs had convinced Sculley to accept the position by challenging him: “Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life?” The line was shrewdly effective, but it also revealed Jobs’s own near-messianic belief in the computer revolution.

Insanely great

During that same period, Jobs was heading the most important project in the company’s history. In 1979 he led a small group of Apple engineers to a technology demonstration at the Xerox Corporation’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) to see how the graphical user interface could make computers easier to use and more efficient. Soon afterward, Jobs left the engineering team that was designing Lisa, a business computer, to head a smaller group building a lower-cost computer. Both computers were redesigned to exploit and refine the PARC ideas, but Jobs was explicit in favouring the Macintosh, or Mac, as the new computer became known. Jobs coddled his engineers and referred to them as artists, but his style was uncompromising; at one point he demanded a redesign of an internal circuit board simply because he considered it unattractive. He would later be renowned for his insistence that the Macintosh be not merely great but “insanely great.” In January 1984 Jobs himself introduced the Macintosh in a brilliantly choreographed demonstration that was the centrepiece of an extraordinary publicity campaign. It would later be pointed to as the archetype of “event marketing.”

Steve Jobs introducing Apple's Macintosh (Mac), January 24, 1984.

Paul Sakuma—AP/Shutterstock.com

However, the first Macs were underpowered and expensive, and they had few software applications—all of which resulted in disappointing sales. Apple steadily improved the machine, so that it eventually became the company’s lifeblood as well as the model for all subsequent computer interfaces. But Jobs’s apparent failure to correct the problem quickly led to tensions in the company, and in 1985 Sculley convinced Apple’s board of directors to remove the company’s famous cofounder.

NeXT and Pixar

Jobs quickly started another firm, NeXT Inc., designing powerful workstation computers for the education market. His funding partners included Texan entrepreneur Ross Perot and Canon Inc., a Japanese electronics company. Although the NeXT computer was notable for its engineering design, it was eclipsed by less costly computers from competitors such as Sun Microsystems, Inc. In the early 1990s Jobs focused the company on its innovative software system, NEXTSTEP.

Meanwhile, in 1986 Jobs acquired a controlling interest in Pixar, a computer graphics firm that had been founded as a division of Lucasfilm Ltd., the production company of Hollywood movie director George Lucas. Over the following decade Jobs built Pixar into a major animation studio that, among other achievements, produced the first full-length feature film to be completely computer-animated, Toy Story, in 1995. Pixar’s public stock offering that year made Jobs, for the first time, a billionaire. He eventually sold the studio to the Disney Company in 2006.

Saving Apple

In late 1996 Apple, saddled by huge financial losses and on the verge of collapse, hired a new chief executive, semiconductor executive Gilbert Amelio. When Amelio learned that the company, following intense and prolonged research efforts, had failed to develop an acceptable replacement for the Macintosh’s aging operating system (OS), he chose NEXTSTEP, buying Jobs’s company for more than $400 million—and bringing Jobs back to Apple as a consultant. However, Apple’s board of directors soon became disenchanted with Amelio’s inability to turn the company’s finances around and in June 1997 requested Apple’s prodigal cofounder to lead the company once again. Jobs quickly forged an alliance with Apple’s erstwhile foe, the Microsoft Corporation, scrapped Amelio’s Mac-clone agreements, and simplified the company’s product line. He also engineered an award-winning advertising campaign that urged potential customers to “think different” and buy Macintoshes. Just as important is what he did not do: he resisted the temptation to make machines that ran Microsoft’s Windows OS; nor did he, as some urged, spin off Apple as a software-only company. Jobs believed that Apple, as the only major personal computer maker with its own operating system, was in a unique position to innovate.

Steve Jobs with an iMac computer, 1998.

Shutterstock.com

Innovate he did. In 1998, Jobs introduced the iMac, an egg-shaped, one-piece computer that offered high-speed processing at a relatively modest price and initiated a trend of high-fashion computers. (Subsequent models sported five different bright colours.) By the end of the year, the iMac was the nation’s highest-selling personal computer, and Jobs was able to announce consistent profits for the once-moribund company. The following year, he triumphed once more with the stylish iBook, a laptop computer built with students in mind, and the G4, a desktop computer sufficiently powerful that (so Apple boasted) it could not be exported under certain circumstances because it qualified as a supercomputer. Though Apple did not regain the industry dominance it once had, Steve Jobs had saved his company, and in the process reestablished himself as a master high-technology marketer and visionary.

Reinventing Apple

In 2001 Jobs started reinventing Apple for the 21st century. That was the year that Apple introduced iTunes, a computer program for playing music and for converting music to the compact MP3 digital format commonly used in computers and other digital devices. Later the same year, Apple began selling the iPod, a portable MP3 player, which quickly became the market leader. In 2003 Apple began selling downloadable copies of major record company songs in MP3 format over the Internet. By 2006 more than one billion songs and videos had been sold through Apple’s online iTunes Store. In recognition of the growing shift in the company’s business, Jobs officially changed the name of the company to Apple Inc. on January 9, 2007.

Steve Jobs.

Courtesy of Apple

00:0003:45

In 2007 Jobs took the company into the telecommunications business with the introduction of the touch-screen iPhone, a mobile telephone with capabilities for playing MP3s and videos and for accessing the Internet. Later that year, Apple introduced the iPod Touch, a portable MP3 and gaming device that included built-in Wi-Fi and an iPhone-like touch screen. Bolstered by the use of the iTunes Store to sell Apple and third-party software, the iPhone and iPod Touch soon boasted more games than any other portable gaming system. Jobs announced in 2008 that future releases of the iPhone and iPod Touch would offer improved game functionality. In an ironic development, Apple, which had not supported game developers in its early years out of fear of its computers not being taken seriously as business machines, was now staking a claim to a greater role in the gaming business to go along with its move into telecommunications.

Health issues

In 2003 Jobs was diagnosed with a rare form of pancreatic cancer. He put off surgery for about nine months while he tried alternative medicine approaches. In 2004 he underwent a major reconstructive surgery known as the Whipple operation. During the procedure, part of the pancreas, a portion of the bile duct, the gallbladder, and the duodenum were removed, after which what was left of the pancreas, the bile duct, and the intestine were reconnected to direct the gastrointestinal secretions back into the stomach. Following a short recovery, Jobs returned to running Apple.

Steve Jobs introducing the iPad at an Apple event, San Francisco, 2010.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images News

Throughout 2008 Jobs lost significant weight, which produced considerable speculation that his cancer was back. (The average survival rate for patients who underwent Whipple operations was only 20 percent at five years.) Perhaps more than those of any other large corporation, Apple’s stock market shares were tied to the health of its CEO, which led to demands by investors for full disclosure of his health—especially as the first reasons given for his weight loss seemed insufficient to explain his sickly appearance. On January 9, 2009, Jobs released a statement that he was suffering from a hormonal imbalance for which he was being treated and that he would continue his corporate duties. Less than a week later, however, he announced that he was taking an immediate leave of absence through the end of June in order to recover his health. Having removed himself, at least temporarily, from the corporate structure, Jobs resumed his previous stance that his health was a private matter and refused to disclose any more details.

In June 2009 the Wall Street Journal reported that Jobs had received a liver transplant the previous April. Not disclosed was whether the pancreatic cancer he had been treated for previously had spread to his liver. The operation was performed in Tennessee, where the average waiting period for a liver transplant was 48 days, as opposed to the national average of 306 days. Jobs came back to work on June 29, 2009, fulfilling his pledge to return before the end of June. In January 2011, however, Jobs took another medical leave of absence. In August he resigned as CEO but became chairman. He died two months later.

Comments: